Duchnovyc labored

for the benefit of many Rusyn people in the Carpathians. He envisioned

a united Subcarpathian nation, which he was trying to uplift — even the

lowest levels of culture. He has come to be hailed as the “national awakener”

of the Carpatho-Rusyn people.

Dobrjans’kyj was a

member of the Hungarian parliament and Austrian government who between

1849 and 1865 attempted to create a distinct Rusyn territorial entity

within the Hapsburg Empire. He formulated a political program calling

for the unity of Rusyns in Hungary with their brethren north of the mountains

in Galicia. He authored several petitions and led a delegation of Rusyns

from Hungary who met with Emperor Franz Joseph in April 1849.

An imperial decree

from Vienna in 1848-49 introduced the principle of the equality of nationalities.

Rusyn was introduced as an official language besides German and Hungarian

in the five counties where they were the predominant minority.

These changes were

shortlived. In September 1850, all civil districts were abolished. Rusyns

were replaced by Magyars and all reforms were eventually nullified. The

Hungarians wanted its citizens to form a single nation—the Magyar nation.

In the late 1860’s the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy came into being.

This meant that the Hungarian Kingdom would be governed by its own laws,

which came out of the parliament in Budapest. Magyar rulers would now

be able to dictate relationships with national minorities, with no interference

from Vienna. Carpatho-Rusyn national revival was stopped dead in its tracks.

Hungary’s primary goal was to maintain as much independence as possible

from the government in Vienna and to consolidate its strength by increasing

the number of Magyars through assimilation of the national minorities.

Law XLIV of 1868—the so called “equality of rights of the nationalities

—was put into practice.

No organization representing

a national minority could legally exist, because this law recognized only

one nation, the Magyar nation. Magyar replaced Rusyn in the schools, which

were then expected to produce patriotic Hungarians steeped in Magyar culture.

Even the churches were affected. Church records which heretofore had been

written in Rusyn by the priest now had to be written in Hungarian. The

Rusyn populace for the most part came to despise its Hungarian masters.

The Rusyns were losing

not only their language but their livelihood as well. Since agriculture

was considered one of the only honorable professions among the Rusyns,

land was passed on to each child who in turn passed it on to their children.

This resulted in smaller and smaller plots of land, which eventually were

too small to sustain the family.

Drying

hay in the Carpathians

The lack of land, low productivity,

and poor methods of cultivation resulted in poverty and semi starvation

of the population. All the great estates were in Magyar hands. The diet

of an average Rusyn consisted mostly of corn or oats, potatoes, mushrooms,

and cabbage. Fat and meat were rarities. (My father has told me of conversations

as a young boy with parishioners who immigrated from Austro-Hungary and

said that the only meat they saw or ate during the year was on the great

feast of Easter.) As a result, health was poor. Tuberculosis, typhus,

cholera, smallpox, throat infections, and other types of common infections

were rampant. One has only to look at the death records from the villages

in which my ancestors lived. Page after page is filled with the names

of people who were wiped out by cholera — it took the young and old. Too

many of my relatives died in infancy or childhood. This was the norm.

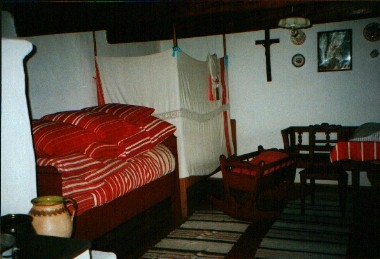

A family typically lived in a one room house, or two families lived in

the same house in adjoining rooms. If they had animals, these lived in

the family house in an adjoining room as well.

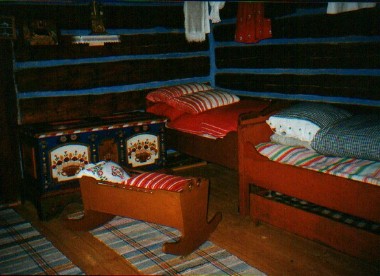

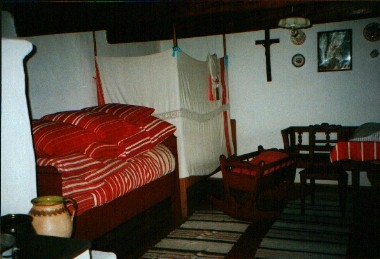

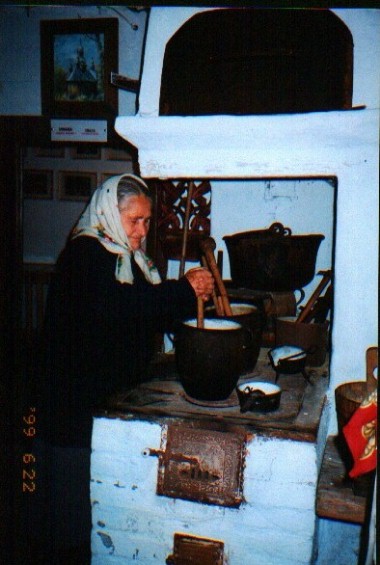

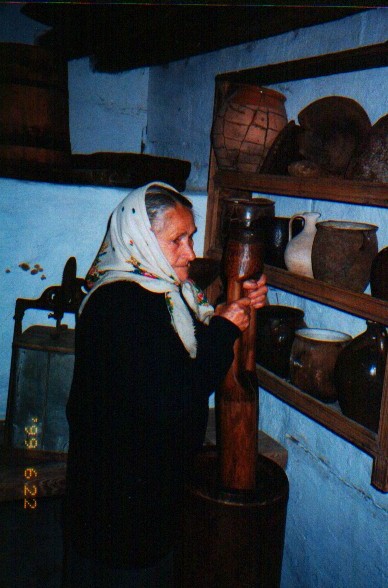

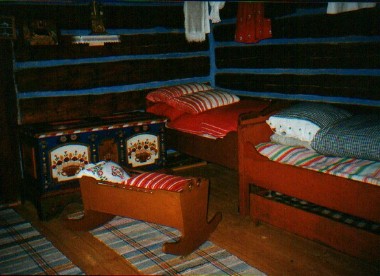

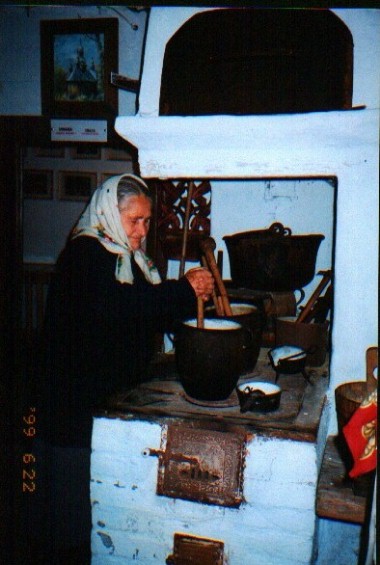

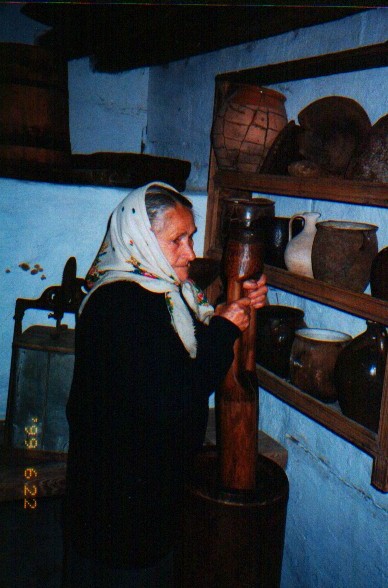

(Here and next photo:)

Inside a typical Rusyn house, Presov

region

The situation seemed

hopeless — the only escape was emigration. From 1880 until World War I,

approximately 500,000 Rusyns (my grandparents and other relatives included)

left the country to escape both the poverty and Magyarization, although

a few thousand had started moving to the Backa region (Vojvodina in present-day

Yugoslavia) in the southern part of the Hungarian kingdom, where Rusyn

colonists had arrived as free individuals as early as 1745. Most left

for the industrial regions of the northeastern United States or Canada.

At the beginning of World War I, Rusyns lacked an educated upper or middle

class and thus were not politically active.

In their new homes,

an aboutface occurred. World War I prevented a further exodus of Rusyns,

many of whom were forced to serve in the Imperial Austro-Hungarian army

where they died or were wounded on the eastern front against Russia or

in northeastern Italy. In the Lemko region during 1914-15, Austrian officials

suspected Lemko Rusyns of treason and deported nearly 6,000 to concentration

camps, especially to the one at Talerhof (Magocsi, “Carpatho-Rusyns: 4”).

At the end of 1918,

a group of American Rusyns under their leader Gregory Zatkovych, a Rusyn-born

Pittsburgh lawyer, met with Tomas Masaryk, the future president of Czechoslovakia,

to discuss the possibility of including an autonomous Ruthenia in the

future Czechoslovakia. In talks, autonomy was guaranteed to the Ruthenian

leaders. Boundaries satisfactory to both were finalized. An agreement

was signed in which the autonomous Ruthenia would include all Hungarian

counties or the parts which were inhabited by Ruthenians. This territory

would have its own governor and administration.

In Hungary, the Ruthenians

and Magyars were also attempting to solve the problem. On December 21,

1918, Law X, “Rus’ka Krajina” (Rusyn State), recognized them as a separate

nationality and gave them the right of self-government in administrative,

judicial, educational, and religious affairs in their territory. Ruthenia

would also have its own national assembly as well as adequate representation

in the Hungarian government.

During the ensuing

months of 1918 and 1919, various Rusyn leaders, including Rev. Emiljan

Nevyc’kyj, Dr. Anton’j Beskyd, and their delegates, met throughout Galicia

and the Presov Region (present-day northeastern Slovakia). They wanted

Lemko Rusyn lands in Galicia and those south of the Carpathians to be

united with Czechoslovakia. On May 8,1919, two hundred Rusyn delegates

met in Uzhorod to form the Central Rusyn National Council. They endorsed

the decree of the American Rusyn Council to unite with Czechoslovakia

on the basis of full autonomy. The results of subsequent sessions undermined

the position of Rusyns in the Presov Region. In the end, the Galician

Lemkos were left to be annexed by Poland. The Uzhorod Council declared

that the borders of the new Rusyn state would be resolved in negotiations

with the Czechoslovak government, and Rusyn leaders in America and Europe

declared that Rusyns in the Presov Regions (northern Spis, Saris, and

Zemplyn counties) be part of an autonomous Rusyn state; but the fact is

that they were placed under Slovak administration. On September 10, 1919,

the Treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye was recognized. Ruthenia was given an

official name Subcarpathian Ruthenia (Podkarpatska Rus’). It would become

an inseparable part of the republic and was promised

the fullest autonomy compatible with the unity of the Czechoslovak state

(Magocsi, Rusyns of Slovakia 67—69).

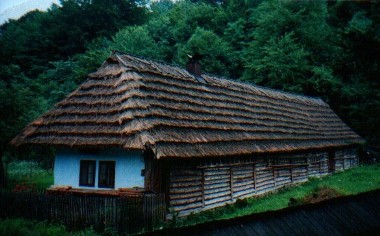

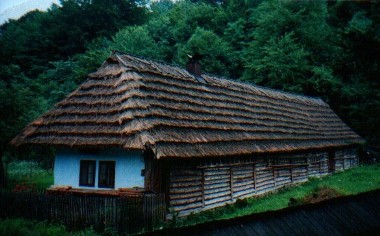

Lemko

house, Poland

What transpired was

that for the first time the Presov Region Rusyns were separated administratively

from their brethren further east. After 1919, Rusyns in Czechoslovakia

did have a province of their own—Subcarpathian Rus’—but the Presov Region

was left under Slovak administration. The Rusyns in the new province had

their own governor and elected representatives in both houses of the national

parliament in Prague; they were considered one of the three state peoples

of Czechoslovakia. They did not, however, receive the political autonomy

they were promised. One hundred thousand Rusyns in the Presov area were

given only the status of a national minority within Slovakia.

In time, the League

of Nations started receiving petitions that the Czech government was not

living up to its treaty provisions and in many cases the Rusyn population

was being Czechized or Slovakized. Subcarpathian Rus’ functioned from

1919 to 1938 with a Rusyn governor and a limited degree of autonomy. When

Czechoslovakia was betrayed by its allies at the Munich Pact and transferred

into a federal state in October of 1938, Subcarpathian Rus’ received full

governing status. Autonomy, however, lasted a mere six months until March

15, 1939, when Germany destroyed what remained of Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

The Lemko Rusyns found themselves under Nazi occupation after Poland was

destroyed in September 1939 and the Lemko Region was annexed to Hitler’s

Third Reich. In the spring of 1941, Vojvodina, with its Carpatho-Rusyns,

was annexed to Hungary. Thus, during World War II, Carpatho-Rusyn lands

were ruled either by Nazi Germany or its allies, Hungary and Slovakia.

During the course

of the war, the Allied Powers agreed that Subcarpathian Rus’ should again

be a part of a restored Czech state. The Presov Region would remain with

Czechoslovakia, the Lemko Region would be part of a restored Poland, and

the Vojvodina would be a Serbian republic within Yugoslavia. However,

the Soviets prepared for the annexation of Subcarpathian Ruthenia. In

June of 1945, a provisional Czech parliament

(without Carpatho-Rusyn representation) ceded Subcarpathian Rus’ to the

Soviet Union, where it became another oblast of the Soviet Ukraine. This

situation lasted until the fall of Communism and Soviet rule in 1989-91.

As people in this part of Europe tell it, they have lived in at least

five different countries but have never left their homes.

Government official

(in Slovak):

We are interested

in Rusyns and we are

willing to support you. But you must finally

decide if you are Ukrainians or Slovaks.

|

Satirical

work of Fedor Vico,

Rusyn

cartoonist and woodcutter

|

During 1945-46 there

were approximately 180,000 Lemko Rusyns in Poland. Two thirds were encouraged

to immigrate “voluntarily” to Soviet Ukraine. In the spring and summer

of 1947 those who remained were driven from their homes by Polish security

troops in what was known as Akcja Visla— The Vistula Operation. They were

forcibly deported by the Polish government to live in the former German

lands of western and northern postwar Poland because they had been accused

of aiding the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (“Nation Building,” 197—209). In

the border regions, many Rusyn villages were destroyed — plowed under

— while others were taken over by Polish settlers. By late l950, Rusyns

began to return illegally to their native mountain villages, and by the

1980’s approximately 10,000 did succeed in reestablishing new households

or in buying back their old houses, although some were blocked by the

Polish government. The Rusyns in Slovakia fared no better, undergoing

intense Ukrainization and Slovakization brainwashing by the Communist-controlled

government.

With the fall of Communism,

a reawakening of the Rusyn community throughout its former ancestral lands

has been occurring. Carpatho-Rusyns in Transcarpathia (former Subcarpathian

Rus’) have called for a return to their historic status as an autonomous

land.

Rusyn societies have

been established to promote Rusyn culture in Slovakia, Germany, Yugoslavia,

Transcarpathia, Poland, the United States, and Canada. The Rusyn language

in Slovakia has been codified since 1995, while it has always been recognized

in Yugoslavia. There is now an active Rusyn press in those countries that

have a substantial Rusyn population (the Rusyn press in Yugoslavia has

been active since the 1920’s); Rusyn festivals of culture, including poetry

and literary festivals, are now widely held throughout eastern Europe.

The Chepa prize (donated by a Toronto Rusyn businessman) is given yearly

for the best example of Rusyn literature. People in the West can now purchase

Rusyn wood carvings, pottery, embroidery, and paintings.

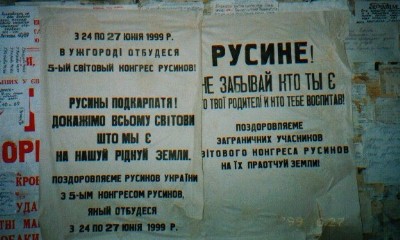

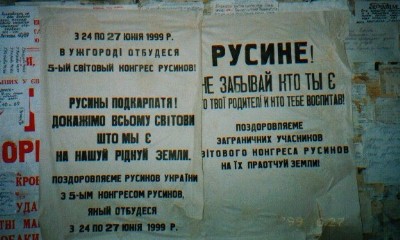

The World Congress of Rusyns met for

the first time on Rusyn soil in 1999 in Uzhorod. The Ukrainian government

has been the only one which refuses to recognize the Rusyn people, yet

the largest minority population in Transcarpathia is the Rusyns. Many

groups are working towards the goal of having the Rusyns recognized as

a minority, including the United Nations and the Unrecognized Nations

and Peoples Organization.

As Petrov so eloquently

states:

The Carpatho-Rusyns have managed

during centuries of oppressions and suffering to preserve their Rus’

soul, Rus’ customs, Rus’ language, and Rus’ name right down to the

twentieth century. A truly just reward for these heroes should not

only be an ardent and enthusiastic concern for them and their welfare,

but also an effort to study these heroes past and to proclaim it to

the whole world. (Petrov 9)

The Rusyns still

face an uphill battle. Many have had to leave their villages in search

of work. One finds only old people in many of them. The church conflict

created by the Soviets between the Orthodox and Greek Catholics may not

heal for years, if ever. The Soviets confiscated the Greek Catholic churches

and designated them as Russian Orthodox. After the fall of Communism,

the Greek Catholics requested that their property be returned. This has

not always happened. As a minority people, they are still persecuted by

much of the populace for who they are — it doesn't matter in which country

they now live. They are still called “shalenij Rusnaci ”— the mad Rusyns

— in reference to their lack of an education during the 19th century.

Racism in Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine towards Rusyns is still present.

It doesn't bode well for these nations that Rusyns from America and Canada

are now returning to find out about their ancestors and to connect with

the homeland. In most cases, they are better off financially

than the local populace. They debunk

the stereotype of the dumb Rusyn.

COPYRIGHT PAUL ROBERT MAGOCSI

1993. USED WITH PERMISSION.

Carpatho-Rusyn

homeland

During the summer

of 1999, I had the opportunity to go on a Rusyn Heritage tour to Poland,

Slovakia, and the Transcarpathian region. We saw firsthand examples of

oppression with visits to a monument commemorating what happened at Talerhof

as well as examples of the Akcja Visla operation throughout Lemko territory.

We learned how hard it is to be a Rusyn in Transcarpathia. However, we

also saw examples of Rusyn revitalization such as the opportunity to sing

Rusyn folk songs with the Lemko Rusyn poet Petro Trokhanovskyi and his

children, to see performances by such outstanding Rusyn groups as Zakarpatskyj

Narodnyj Choir in Uzhorod, and to attend the Rusyn Festival of Culture

and Sport in Medzilaborce.

Andy Warhol

Museum in the city Medzilaborce

Medzilaborce is home to the Andy Warhol

Museum. Andy Warhol, nee Varhola, was a Rusyn whose parents came from

the village of Mykova. The museum was established as a memorial to him

and his family. Mykova doesn't look as if it has changed since Warhol’s

parents immigrated to the United States. We saw and were able to purchase

examples of Rusyn craftsmanship. I had not been aware of the Rusyns’ outstanding

artistic talents in woodcarving, pysanky (dyed eggs covered with beeswax

designs), and embroidery. I felt at home on the tour; in a sense I was

at home. I was very proud of my people for their courage and strength

in enduring so much oppression throughout the centuries, proud that so

many had had the presence of mind to leave the “old country” for a better

life. As Karen van Kumes stated so succinctly in an editorial in the August

12-24,1999, edition of The Prague Post, “A government may strip you of

your citizenship but never of your nationality.”

|

Ja

Rusyn byl,

Jesm'y budu,

Ja rodylsja Rusynom,

Cestnyj moj rod ne zabudu

Ostanus’ jeho synom!

|

|

Typical house in Carpathian

Mountains

|