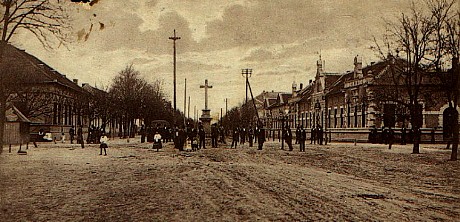

A couple of items in the Homeland

museum in Ruski Kerestur

Ruski Krstur in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes - Yugoslavia

(1919-1941) underwent several dramatic periods typical of all Ruthenians'

lives in these parts in general. The first one was economically difficult

because the first gap between the better-off and the poor grew wider.

The increasing number of poor and landless families resulted in an economic

emigration to Canada, USA, South America and France. The wealthier village

land-owners were still far from being rich in the capitalist sense. In

the stage of the initial accumulation of capital, the fact that they were

a minority was an obstacle because the system of privileges in money turn-over

and profit investment was not conducive to their needs; the privileges

were reserved for the capital owned by the state-building nations. The

Ruthenians of Ruski Krstur at that time, and forever after that, understood

a deeper truth or a personal historical experience which was to repeat

itself throughout the 20th century, namely: that only an economically

independent nation, individual, social class or a community can be free.

An entrepreneur or a citizen as a member of a state-building nation and

the one belonging to a minority are not in the same position as economic

subjects because it is only towards the former that the state is inclined

through its policy of economic privileges and stimuli. In addition to

the mechanism of mostly direct assimilation or systematic acculturation

which was typical of the life of the Ruthenians at Ruski Krstur in Hungary,

there appeared another economic and social mechanism supportive of the

former two - the national state protectionism. In the social life, given

this situation, the Ruthenians in Yugoslavia, Ruski Krstur, consolidated

the issue of their language, and reaffirms their national and religious

identity, realizing that, in addition to the economic independence, culture

was the most powerful preserver of one's identity; there was a growing

number of literary works written in Ruthenian and from a Ruthenian point

of view and the first national and cultural organization was founded on

August 2,1919, called the Ruthenian National Society of Education.

In 1923, Kosteljnik codified The Grammar of the Bačko-Ruthenian Speech.

Besides leaning onto the Yugoslav cultural and literary context, the Ruthenians

at Ruski Krstur had very close ties with the Ukrainian literary and cultural

life. The contribution of the Ruthenian national society of education

contributed to the development of the cultural and national identity by

1) raising the consciousness about the potential of the Ruthenians to

self-organize, i.e. to become an historical subject in this part of Europe,

2) insisting on an historical, cultural and national entity within an

overall Ukrainian cultural and national integration, 3) asserting that

the Ruthenian cultural tradition belongs to the East-Slavic cultural tradition

and needed integration in the South-Slavic cultural space, 4) claiming

that they should not turn their back to the language Ruthenians spoke

from birth, and that, although it was quite logical to receive elementary

education in that language, it would not harm intellectuals to speak Ukrainian

among other languages as well. The rightist trends at the time were not

typical of this Society only, but surfaced among other nations of Yugoslavia

as well, on the eve of World War II.

Rusyn costume from the middle

of XX cenury

After World War II, till 1991's when the Serbo-Croatian war began,

the Ruthenians of Ruski Krstur believed that their historical rights and

needs would never be disputed again and that their life would only depend

on their creative potential, common sense and their capacity to self-organize.

Most of them accepted and experienced the socialist Yugoslavia as their

own motherland. Disputes over the destiny of Yugoslavia, in the late 80's

made them fell uncertain and uneasy, because they did not have a spare

fatherland in some kind of their own republic which could go on living

as their national state, as the case would be with the state-building

nations of the Serbo-Croatian civil war, the Ruthenians of Ruski Krstur

found themselves in a dangerous sphere of suspicions, not arising from

their liability, but out of insufficient knowledge or ignorance and aversions

that other people derived from it. They found it hard to accept the possibility

that their destiny might be decided by someone who neither knows enough

nor wants to learn about the people about whom he is to decide. Publicly,

the question of equal rights of the state-building nations versus the

minorities is openly avoided. Irrespective of the doubtlessly notable

results in culture and education, which have amazed the world, the hope

of the Ruthenians of Ruski Krstur and Vojvodina as a whole grows smaller

faced with the reality of the power and logic of numbers and the laws

based on them. Their constructive and loyal attitude towards the authorities

suddenly ceases to be a guarantee for a deserved life and development.

Without the power of numbers and masses, the Ruthenians of Ruski Krstur

and Vojvodina will have to play the part of a litmus paper indicating

the validity of the current political practice and the authority of those

in power. At the same time, they have ceased to control their own destiny.

They have been reduced to being the citizens obliged to submit to the

political and public will of the state-building nations and the current

government. As a result of the influence of politics on the economy, and

without a commune with a majority of Ruthenians, but only a local community

within the commune of Kula where the arguments of their own political

will as a special ethnic community have been too weak, the Ruthenians

of Krstur have been forced to ask for what belongs to them as a collectivity.

Without economic strength, no collectivity can be free. In the 70's and

80's, the Ruthenians of Krstur had a number of achievements in culture

and education, not because before and afterwards they lacked creativity,

but because the conditions changed and creativity came to depend on the

good will of the authorities - sometimes alienated from the Ruthenians.

The agrarian reform following World War II did not fully include them

either. It is true, though, that a part of the population moved out to

Gunaroš, i.e. Novo Orahovo; over the years, they gradually blended with

the social, cultural and linguistic milieu of the more numerous and historically

more resilient nations. Even though they know how to cultivate land, they

are still knocking on the door of the government, which, much like the

one 200 years ago, did nothing of what had been expected and promised.

Funeral of Veruna

Pankovič nee Papuga (in June 1930)

Back row from left to right:

wife of Štefan Papuga Teštvir, Ilja Dudaš nee Papuga, Ana Tirkajla nee

Papuga, Marja Dudaš nee Papuga, Ana Budinski nee Dudaš, Sofija Mudri

nee Papuga, Ana Pankovič, her son Danil Pankovič.

Front row from left to

righ: Marja Džudžar nee Tirkajla, she holds in her hands his younger

brother Vladko Tirkajla, behind them there is Marja Kanjuh nee Dudaš,

Olga Makaji nee Papuga and her sister Amala Medjesi nee Papuga. On the

right is Janko Pankovič, later electrician in Ruski Kerestur (died May

2002)

Towards the end of the 80's, the Greek Catholic Church reappeared on

the historical scene, although it had lost importance among the citizens

of Ruski Krstur. Thinking and acting according to the centuries-long standards,

the Church has made it clear that in the dimensions of both the natural

and religious life it supports the unifying factors of Ruthenians and

Ukrainians and not those divide them, although it has not denied the need

to respect and cultivate the difference in their cultural and national

identities.

The last several decades have been marked by some achievements, searches

and break-downs in education and culture (theater and folk dances) and

efforts aimed at fortifying the Ruthenian national identity at Krstur.

Members of family Budinski (Brugoš, Pinter), 1972

Back row, from left to right: Miron Budinski (1929), Vladimir Budinski (1950), Julin Budinski (1932), Janko Budinski (1935), Mihajlo Budinski (1946)

Front row, from left to right:

Marija Budinski, maiden name Rac (Krenjicki), Marija Budinski, maiden name

Sopka, Natala Budinski, maiden name Birkaš, Dana Budinski, maiden name Glidžić,

Olgica Budinski (1955), Senka (Femka) Budinski (1959)

Seated, from left to right:

grandfather Jakim Budinski - Brugoš (1907), Saša Budinski (1963), and grandmother

Melana Budinski, maiden name Bodjanjec - Davidova (1910)

In the post-war period, even though education has been offered in Ruthenian,

the cultural and national identity can best be cultivated in the classes

of the Ruthenian language and literature. The history of Ruthenians has

been taught very little in general history classes as determined y the

curriculum. The Ruthenian language and literature teaching is specific

and best suited to the indirect cultivation of the national awareness.

This is why the elementary and secondary school readers and literary passages

in them have been designed for the most direct cultivation of the national

and cultural identity.

The Ruthenian national and cultural identity have been promoted

after the war and has found its expression in the spheres of culture,

education and religious life. The cultural life at Ruski Krstur gathered

together professional and amateurs around two cultural institutions: "The

Red Rosa" - a cultural festival of the Ruthenians and Ukrainians

of Yugoslavia and "The Memorial of Petar Riznič Djadja" -

a theater festival. The anthem "The Red Rose", after which

this festival was named (founded in 1961), is a composition by J. Siv?

- "Roses, Red Roses". In the 30 years of its activity, "The

Red Rose" has developed a character of its own through regular events:

art, ethnographic and historical exhibitions; "The Red Bud"

- a children's festival of music and folk dances; poetry reading and music

festival "Heart-beat"; "The Red Rose" competition

in singing and composing folk and pop music and awards presentation; "Echoes

from the Plain" - an annual festival of the Ruthenian art and culture

societies with humorous sketches; a seminar on various subjects in the

Ruthenian history and culture; "Estrada bratstva" - music and

folk dance festival of the renowned Vojvodinian and Yugoslav nations and

minorities, as guests from Ukraine and Czechoslovakia; "Keresturijada"

- a pop/rock groups competition; the greatest value of "The Red Rose"

is that it enables, at least once a year, the Ruthenians and Ukrainians

in the diaspora to meet and socialize. This is the time when the local

people put a lot of effort to host the festival; at the same time, they

build their confidence and promote their culture.

RUSYN GIRL IN PINK

Art Gallery of Sava ?umanovi?, ?id

In the course of 20 memorial festivals of Petar Riznič Djadja (the first

took place on April 6-11, 1969), the total of 207 plays were performed

(187 amateur and 20 professional). The Ruthenian amateur theater and drama

workshops staged 153 and visiting theaters 54, 170 of them for grown-ups

and 37 for children. Among the authors, there were 124 Yugoslav, 83 foreign

playwrights and 28 contemporary Ruthenians. According to the type of performances,

61 were classical, and 146 contemporary. Out of the 207, 142 were in Ruthenian,

42 Serbo-Croatian, 12 in Ukrainian. 9 in Slovakian, 1 in Rumanian and

1 in Hungarian. Out of 153 Ruthenian and Ukrainian performances entered

for the competition, 131 were directed by Ruthenian and Ukrainian directors,

and for the remaining 22, other directors were engaged. In the 20 years

of its activity, the drama festival "Petar Riznič Djadja" engaged

more than 4,000 actors and directors and about 1,000 organizers.

"Ruski Krstur - Chronicle and History (1745-1991)"

by

Dr Julijan TAMAŠ - (494 pages, printed in 1992)